For many years, I have referred to myself as a “visual learner,” finding I have better success learning, remembering, and understanding things when I can actually see them working. I have great success remembering information when there’s an image associated with it, but sometimes it’s enough just to remember where a point/sentence/block of text was located in the textbook, as that can be enough for me to visualize the information I’m looking for. Visual elements can be full-on graphic images, how information is arranged, or even bolded/italicized text.

Going through the school system, I found that there were never enough visual accompaniments to what our teachers were telling us, so I struggled to keep it all straight and to visualize it myself. Learning about the dual-code theory of learning (in EDCI 336 and ED-D 401) has been especially relevant because, while I think nearly everybody learns best with complementary visual and auditory information, I don’t think many people consciously reflect on that, and I certainly don’t think many educators are conscious/deliberate enough in their use of visual elements to enhance auditory information, and vice versa. In a perfect world, there would be no distinction; all information would contain complementary visual and auditory elements.

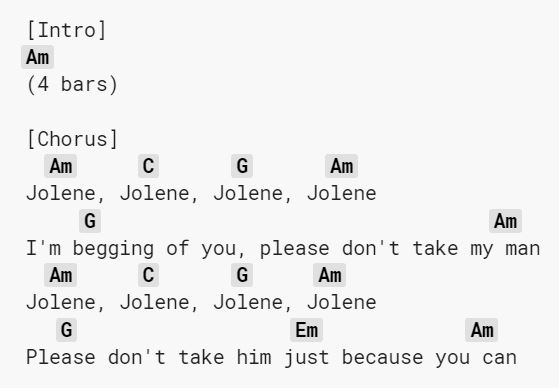

Our discussions in class, and my own learning experiences, have me thinking more about exactly what constitutes visual information, and whether visuals actually help with information processing and retention. To ground my reflection in something you can visualize, take the beginner guitar chords to play “Jolene” by Dolly Parton, pictured below:

Visually, this is a moderately useful resource, telling me which chord is being played at a given time. However, it does not make explicitly clear exactly when a chord is played. The first line makes it seem like each chord is played in the middle of the word, but listening to the song–combining auditory and visual information–confirms this. The Aminor, C, G, and Aminor are played on the second syllable of each Jolene, so a chord is played at each bold location: Jo-Lene, Jo-Lene, Jo-Lene, Jo-Lene. For the second line, visually I’m inclined to think the G is played on the second syllable (I’m begging you), and the Aminor on the very last one (my man). Again, the auditory information confirms this.

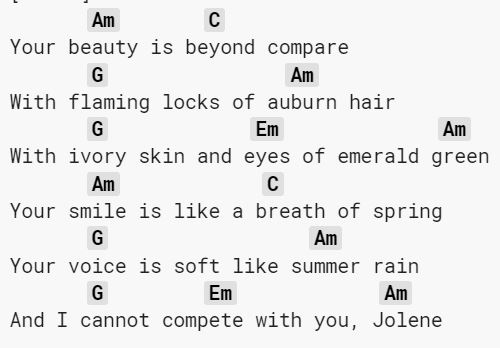

Yet even for this incredibly beginner song, the visual information isn’t enough to properly play it:

For each line, the first chord is played on the second syllable (Your beauty, With flaming, etc.). This is visually apparent until the 6th line, where visually, it seems the first chord should be played on the third syllable (And I cannot). I think to myself, perhaps “And I” are sung quickly so as to be one syllable. After all, there is an auditory pattern playing it that doesn’t fit the visual pattern looking at it. Yet by listening to the song and to tutorials on how to play it, I know that G should be located over the I (And I cannot).

Crucially, these guitar tabs are not meant to provide all the information to play the song. They tell you which chord is played for which section, and sometimes at what time, but one must actively listen to the song to know the rhythm/frequency that chord is played at until the next chord is played. I remember looking over my friend Nicole’s shoulder when she pulled up “This Town” by Niall Horan on a guitar tab app; I asked her how she knew how to play the song from the information in the tab, because it seemed too sparse to do so, and I was right, because she said it was useless without pairing it with the auditory song itself (at least to faithfully reproduce a song’s guitar).

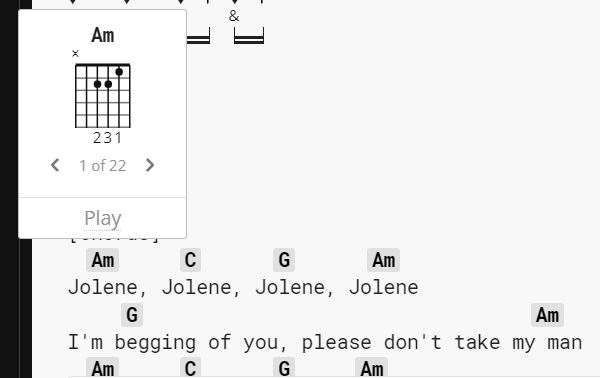

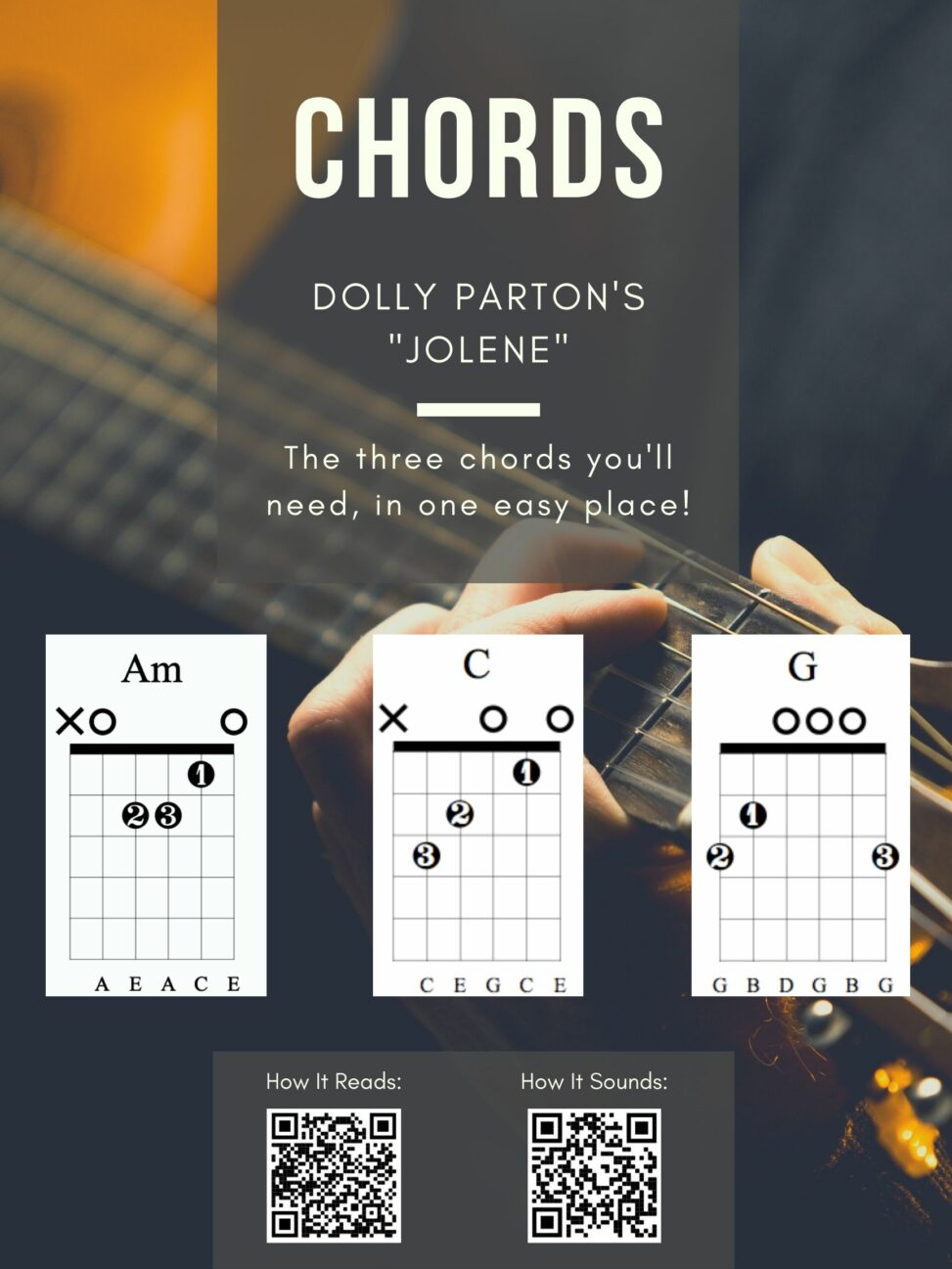

I will give further credit to the tabs as a visual resource because they also contain visual depictions of each chord in case you forget. In the browser, they display whenever the mouse is hovered over a chord (pictured below) while on mobile devices all the necessary chords are pictured at the top of the page.

Ultimately, neither the tab chart nor the audible song are as effective individually as they are when combined, and it isn’t close. If I played it with just the song, I would have no idea which chords were being played when, and if I played it with just the tab chart, I would be misled by line 6 of the first verse. I also wouldn’t know to play each chord 2-4 times, rather than the once depicted (something I only know thanks to the dual-coded tutorial below).

Unfortunately for me, no amount of combined auditory and visual information can overcome my inexperience, and the weak muscle memory I’ve started to develop. But having auditory and visual information means I can practice efficiently and effectively, so that that muscle memory comes in a much shorter time than it would if I only have one form of information to work with. So I will continue to incorporate useful, helpful visual information to auditory presentations, and vice versa, in the hopes of streamlining and increasing student learning, rather than overstimulating and confusing them.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.